There is usually a two-time rhythm in the generative process. First, a stage of system design. Second, a moment when the automaton springs into action, like the stormy night when Doctor Frankenstein’s unholy creature received the spark of life. The former is an instance of imaginary projection and careful execution, more classical in its outline. The latter is the novel scene, when the artist retreats, becomes a spectator of their own work, and watches as events unfold. One possible measure of the success of the generative process is to what extent the automaton proves capable of surprising its own creator: how rebellious or unpredictable the creature becomes when set in motion.

This two-time cycle can take place just once or go over many iterations, becoming a trial-and-error procedure. The artist and the automaton become involved in a sort of dialogue: with each run the system does things that compel the human to change some things that make the system do different things, and so on. This back-and-forth drives a process of evolution, or at least semi-random drift, in a space of possibilities, towards a destination that could not be foreseen by the artist (or the automaton) beforehand. They could only reach there together.

In short, generative art can be regarded as a creative collaboration between a human and a non-human agent. The outcome is something neither of them are capable of doing on their own: a hybrid work, which is not the mere display of the technical capabilities of a given apparatus, nor the direct exteriorization of a human intention, but something in between, in tension between the human and the non-human, like an artistic cyborg.

6. Machines and systems

We have used the word “machine” a few times to talk about the automaton. But that might be misleading: in any case, the automaton would be a very particular sort of machine. First, because the word “machine” makes us think of a concrete, heavy, complex piece of matter that is taking up space somewhere. But the essence of the automaton is in the software, not in the hardware. Its soul is given by the rules it embodies. Second, the power of the machine is typically doing the same many times, with great speed and efficacy. But the automaton does things that are all different.

During the Industrial Revolution, machines enabled a quantitative explosion in the production of goods that transformed the world radically. We all know that. However, there is an associated fact that might be less obvious: namely, the qualitative reduction in the variety of objects around us. Suddenly, our coats and carpets and cups and chairs were all identical. The diversity and individual character that comes with crafts and handmade work was lost. The industrial machine is linear, predictable, and transparent in its operations, because its very nature lies in repetition. We expect from it to behave exactly the same every time, and when it doesn’t, then we are in trouble: the machine is broken. Machines brought forth an age characterized by the multiplication of the identical.

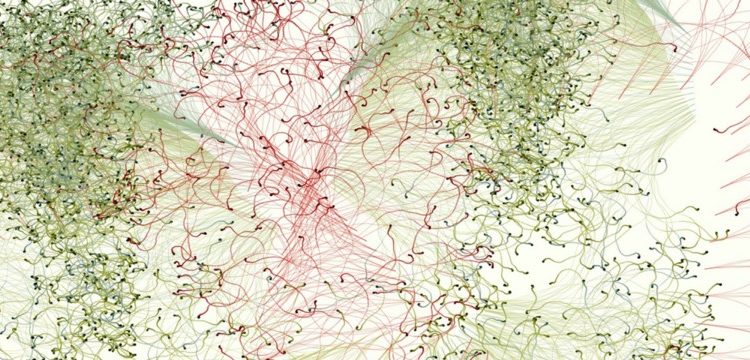

On the other hand, the automata or, in Burnham’s terms, the systems, are recursive, opaque, and variable. Their inner workings are often too complex for thorough explanation. When set in motion, there are feedbacks, interactions and non-linear processes that render it unpredictable. The gears and levers are not plain to see: it tends to be a black box. Its output is equally variable. The systems open before us a new landscape: the automated production of difference, the explosive multiplication of the unique. The “mass production” of the industrial age is converging now on the production of the particular that was typical of the artisan’s shop.

The insane productivity of the automaton is a source of fascination, but it can also become a problem for the generative artist. There is often an “embarrassment of riches” that leaves us with the difficult task of choosing what, from an overly abundant output, are we going to actually show as a work. The work is, in a certain sense, the entire space of possibilities created by the system. But that cannot be shown. It is sometimes so vast that even we, as artists, can only explore a few trails and regions of it, descend on it in limited incursions guided by chance and instinct. We can choose to present the automaton as an interactive application that users can navigate, and thus, so to speak, pass on the problem to the public. But many times we find ourselves in the situation of having to capture and select particular instances of the countless things the system can do, and that always feels arbitrary, like an undue human intrusion on the wild freedom of the automaton. As we noted before, those captures are just samples standing as representatives for the rich world of the possibilities they come from.

7. A second nature

Of course, nature itself is “generative” in the sense we have been describing. It is indeed the epitome of generativity. No two trees are exactly alike, no two leaves of the same tree are identical. However, we don’t usually speak of trees as “generative”, because that’s a qualification we reserve for human creations. Art is a human affair, and generative art is too. We could say the “creative collaboration” between a human and a non-human agent is, at the end of the day, not really horizontal, not a gathering of equals. There is an essential asymmetry, because the automaton is made by a human, and it only springs to life when and for as long as the human decides. The naked truth is, the human is still in control.

All that is true. Generative art is, in a certain sense, still all too human. But even a short moment of surrender, a small space for the autonomy of the system, is enough to change everything. As we tried to show, the canonical places of the artist and the work in the traditional paradigm of artmaking are brought down by this intrusion of the agency of non-humans. All of a sudden, art is not any more about making beautiful or sublime or radical objects, but about exploring systems: going for a walk in the universe that lies beyond the limited realm of human stories, wishes and fears.

Generative art is also part of the process by which technology strives to resemble nature more and more–moving away from the rigidness and obdurate insistence on the same of industrial machines, towards the adaptability and variability of complex systems. Step by step, human inventions acquire for themselves characteristics that were the privilege of life. As this happens, the balance of power in the “creative collaboration” changes. Automata become more autonomous. Human participation becomes ever smaller. It is perhaps not so crazy anymore to think of a future when automata don’t need us at all to live their lives and develop their creations. At that point, technology would become a sort of “second nature”, and art would cease to be an exclusively human affair.

These days, this trend is visible in the quick succession of amazing developments happening in the field of the so-called “Artificial Intelligence”. Neural networks and deep learning technologies are conquering territories that were, not long ago, undisputed human domain. They can now drive cars, diagnose cancers, speak and listen, beat any of us at chess and go, write texts that make sense, etcetera. A few years ago, the Deep Dream experiment by Alexander Mordvintsev [7] surprised many of us by showing they can also do something that feels intimately human. They can hallucinate: that is, see things that aren’t actually there, but that they are trained to see and can reinforce in a feedback loop, producing images that are not a representation of anything external, but a strange visual record of the “ideas” that are somehow encoded in that digital mind.