Data Scientists and AI practitioners in the near future will not only have to be well versed with the Engineering that goes into these applications, but also have to consider ethical, legal, and philosophical implications of these solutions.

It can be safely asserted that today’s world is being profoundly influenced by Data Science and Artificial Intelligence, and that the trend will accelerate and persist for the foreseeable future. With new datasets, new modes of information processing and analysis, and increased quality and quantity of computational resources, the list of use-cases for which Artificial Intelligence can be deployed cost-effectively today is only increasing. And as investments, talent, and infrastructure continue to make a beeline for the sector, the timeline for bringing potential use-cases in various industries and functions, from conceptualization to production grade solutions, is only going to become progressively shorter.

Seemingly locked-in-step with the blitzkrieg of novel developments in the AI world are a growing list of concerns about AI implementation from a wide range of stakeholders, including AI Practitioners, Businesses, Governments, Labour, etc. As prominent examples of misuse, misapplication, maladaptation, miscalculation, and mal-governance due to AI applications increase, so do calls for regulation from across the socio-legal, business, and political spectrums.

As prominent examples of misuse, misapplication, maladaptation, miscalculation, and mal-governance due to AI applications increase, so do calls for regulation from across the socio-legal, business, and political spectrums.

Not all these concerns stem from vague fears of an AI super-intelligence reshaping societies, from real fears of the weaponization of AI, or even from far-fetched notions of what Artificial Intelligence can achieve today. Indeed, even legitimate businesses developing legitimate AI-based applications for legitimate customers fear the potential for abuse, and are looking towards public policy and civil society for frameworks to guide future development. For Businesses, the risks of proceeding without any standards or regulations are already seen to be too high.

For Businesses, the risks of proceeding without any standards or regulations are already seen to be too high.

The sentiment was also shared by the President of Microsoft, Brad Smith, in an extraordinary blog post in the July of 2018. Brad expressed concerns about the easy access to Facial recognition Technology, an area that falls under the ambit of “Computer Vision” in the AI world, and which even Microsoft sells as part of its Azure Cognitive Services offerings. He has openly called for “thoughtful government regulation and for the development of norms around acceptable uses” — a remarkable ask from a Technology industry behemoth whose sector has traditionally feared the potential of regulation to curb business innovation.

The President of Microsoft’s request for regulation was not an example of the bandwagon effect, nor one of mere tokenism or virtue signaling, as was seen by his comments after the recent passage of Facial Recognition Legislation by the State of Washington in 2020. In a blog post dated March 2020, Brad stuck his neck out and hailed the law, which he called a “landmark” and a “significant breakthrough — the first time (that) a state or nation…passed a new law devoted exclusively to putting guardrails in place for the use of facial recognition technology.”

The challenge for Policy makers is multi-fold. They are already seeing how AI is reshaping their own respective economies and societies, and that of the larger world. They know that they need to act before they are forced to kill the golden goose, and they also hear the calls for AI Regulation from a broad range of constituents. But they also find themselves in an age-old challenge that harkens back to the Free-Market vs the Controlled Economy debate — to create a regulatory environment where businesses and society can freely and transparently use AI/technology to improve productivity and create jobs, while also creating a regulatory environment where fundamental rights, rule of law, democracy, and the social contract can continue to evolve positively and thrive.

The field of AI is advancing quickly, and even expert practitioners find it difficult to keep pace with the many developments occurring across all of its sub-domains.

Compounding this challenge for lawmakers are two big problems:

For one, the field of AI is advancing quickly, and even expert practitioners find it difficult to keep pace with the many developments occurring across all of its sub-domains. A very real Analytical Translation gap does exist in the above context, and it hampers the ability of Policy makers to truly be conceptually informed about latest developments as well as become proactive about regulating AI properly. In a famous instance, when the CEO of Tesla, Elon Musk, first asked members of the National Governors Association to regulate AI Development in 2014, a Republican Governor from Arizona retorted that “As someone who’s spent a lot of time in [my] administration trying to reduce and eliminate regulations, I was surprised by your suggestion to bring regulations before we know exactly what we’re dealing with.”

A great deal of AI development (from data gathering, transmission, and pre-processing to model development, deployment, and governance) is highly contextual, and often difficult to replicate even in similar contexts. This makes it challenging for Researchers to assess these solutions and provide evidence-based policy recommendations.

Secondly, a great deal of AI development (from data gathering, transmission, and pre-processing to model development, deployment, and governance) is highly contextual, and often difficult to replicate even in similar contexts. This becomes a problem for Researchers who wish to assess the cost-effectiveness or socio-political implications of these technologies, and in turn on Policy makers looking for evidence upon which to base their policy recommendations.

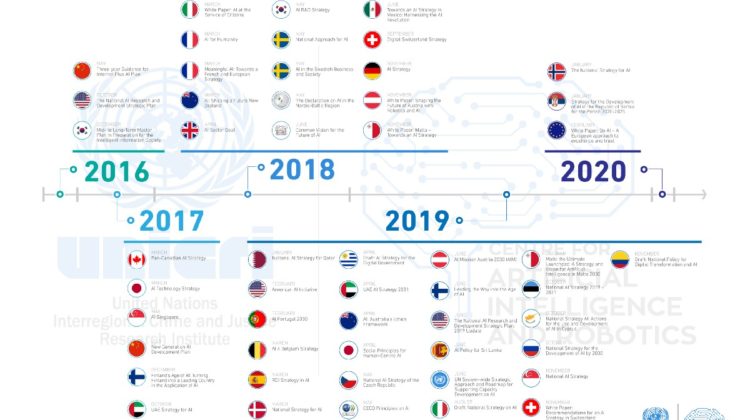

Despite all of the above limitations, much progress is underway within the realm of AI Standards, Principles, and Regulation. As of 2021, several Governments, Multilaterals, Technology Firms, Think Tanks and others have already published a host of influential whitepapers, guidelines, strategies, action-plans, policy papers, and regulations on the subject.

The European Union, for instance, is guided by a High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence that has published two influential papers in 2019 on the “Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence” and “Policy and investment recommendations for trustworthy Artificial Intelligence”. The European Commission has also published a “White Paper on Artificial Intelligence — A European approach to excellence and trust” in 2020 that outlines the EU’s approach for a regulatory framework for AI.

Similarly, the regulation of AI in China is mainly governed by the “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan” of 2017, an “Artificial Intelligence Standardization Whitepaper” in 2018, and a paper on “Governance Principles for a New Generation of Artificial Intelligence” in 2019.

India’s AI regulatory framework is currently being guided by a “National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence” published by the Niti Aayog, the successor to its erstwhile National Planning Commission.

Other important national initiatives include those within the United States, whose National Science and Technology Committee on Technology published a paper on “Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence”, the United Kingdom, whose Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence within the House of Lords published an “AI in the UK: ready, willing and able?” report in 2018, and other such initiatives across France, Singapore, Germany, Japan, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Sweden, Finland, Portugal, etc.

A fair assessment of AI Standards and AI Regulation today will admit that it is still in its early stages, and that there will be a long way to go. It is also equally true, however, that regulation is indeed on its way. It will not be too far-fetched to believe that the Data Scientists and AI practitioners in the near future will not only have to be well versed with the Engineering that goes into these applications, but will also have to consider legal and philosophical implications of these solutions.

The shape and form in which future Regulation will eventually arrive to all parts of the AI world will depend upon how practitioners go about developing, deploying, and shaping the usage of AI in the real-world. If they succeed in a manner that convinces a broad spectrum of stakeholders, the field will remain vibrant and yield extraordinary economic benefits for the world.

The shape and form in which future Regulation will eventually arrive to all parts of the AI world will depend upon how practitioners go about developing, deploying, and shaping the usage of AI in the real-world.

An excellent example of where this has worked in the past can be seen after the passage of the 1974 Fair Credit Billing Act by the United States’ Congress. In the early 1970’s, the fledgling Credit Card Industry routinely and shortsightedly held cardholders liable for fraudulent transactions, even if their cards had actually been lost or stolen. Taking cognizance of the matter, the legislative passed the Fair Credit Billing Act whereby limits were imposed on cardholder liabilities. This effectively made it impossible for Credit Card firms to pass on the costs of fraudulent transactions onto customers.

It was here that savvy AI Practitioners and Leaders of the era saw opportunity, and would eventually create the famous use case of AI-based Fraud Detection for Card transactions that is now ubiquitous across the Industry. Their solution would be one of the first ever commercial applications of neural networks in a production setting, and it had the transformational effect of not only reducing losses for the Businesses but also increasing public trust in the new payment system of the age.

If, however, AI Practitioners fail to deploy Principled AI, and their solutions alienate a large number of stakeholders along the way, regulation will be forced upon them. Such regulation will not always be positive or rooted in trust and in such situations, it will be an uphill battle to convince Policy Makers and Civil Society to engage in good-faith dialogue.

There are countless examples of some of the most promising technologies and industries being regulated into a soporific torpor, such as in the case of Nuclear Power, Coal-Intensive Industries, Aviation, Pharmaceuticals, etc. Within this context, it would not be unreasonable to say that a significant portion of the blame lay with the Practitioners for failing to address the needs, aspirations, and fears of society-at-large with respect to these technologies and domains.

If all it takes to ensure that the AI Revolution is a Sustainable Revolution is by demanding that we stakeholders grapple with a few uncomfortable Ethical, Legal, and Philosophical Questions alongside partaking in the many joys and benefits of technology innovation, it does seem like a small price to pay.