A few days before his inauguration, President Biden outlined a bold $1.9 trillion plan to address the COVID-19 pandemic his administration would be inheriting. One quote he makes, at the 2:38 mark of the hyperlinked video, has stuck with me ever since:

And the emptiness felt by the loss of life is compounded by the loss of our way of life. During this pandemic, millions of Americans, through no fault of their own, have lost the dignity and respect that comes with a job and a paycheck.

I keep thinking about that last sentence, the dignity and respect point he makes. No matter one’s politics or personal feelings towards Biden, everyone should agree that losing a job, being unable to find work, or having to settle for underemployment is almost indescribably disheartening. The reality of recession is that many experience food insecurity and/or suicidal depression, and economists thus have a significant obligation to quickly restore economic normalcy. But admittedly, that’s only a small part of the reason why I have been thinking about that quote.

The loss of dignity and respect within occupations is something that I have been obsessed about ever since I moved out West to do economic research. Here, I was exposed to new ideas concerning automation, AI, and the future of work, and though I still have so much more to learn, innovative technologies and the implementation of machine intelligence is an overall societal positive in my mind. There is concerned buzz around increasing automation, perhaps best exemplified in the conversation around Andrew Yang’s “Freedom Dividend”, that is entirely justified, but I find that it fails to address something in the future of work: the fulfillment a worker will get from a job, especially if that job is not completely automated away.

A lot of the dignity and respect that comes from working is a direct result of what one does. For example, if you love programming and creating software, you would love being a software engineer. In some sense, how productive you are as software engineer affects how much you love your job, but your productivity is only one part of the fulfillment puzzle. How is the company culture, does your boss care about your personal growth, are you intellectually stimulated, etc.? Job fulfillment and satisfaction is so much more than just employee productivity numbers. Establishing that (1) there has not been substantial aggregate labor market effects so far because of automation and (2) that AI implementation now serves to only automate certain tasks within jobs, I want to ask the following question: Will the introduction of AI tools and the changing of job tasks ultimately change job satisfaction levels in the future? Also, how can we design AI to maximize job fulfillment?

Economic literature misses that mark for me, although I may not be looking hard enough. We seem focused on productivity implications reminiscent of the Solow Productivity Paradox. Some papers examine important organizational changes associated with automation, like this Dogan et al. paper, but will employees of all skills levels still find meaningful work in these new organizations? Will American way of life change substantially in this sense, risking the ability of everyone in the future to find dignity and respect through their work?

Perhaps that introduction was a bit rambling. I guess a great way to illustrate my point, mainly because I am not the best at explanations, is through an example of AI being used today.

Airport Security and AI

As an American, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) being inefficient at their job has just been a fact of life. Even though the confiscation of contraband and improvement of flight safety is a societally important task, the agency has been shown to be a notoriously poor performer over the years. The introduction of image recognition AI here, therefore, makes sense, and can boost overall safety and TSA worker productivity. In fact, all security checkpoint personnel using the technology would perform better, regardless of the venue or country.

But what happens to airport security workers now? Their jobs being not completely automated away, they essentially become glorified bag searchers, reliant on AI machine predictions. An argument can be made that now TSA workers can focus on customer service and receive more training to efficiently search luggage, but my question is whether they would still enjoy working in that job (or enjoy the job even less than they already do)? Really, would any person enjoy an airpot-luggage-searching, customer-focused job, especially considering traveler attitudes and frustrations? I am sure the answer lies somewhere in the middle, where a share workers will enjoy the changes and the other share will not. But that reality spurs another question: Why will some people like working with AI and others not?

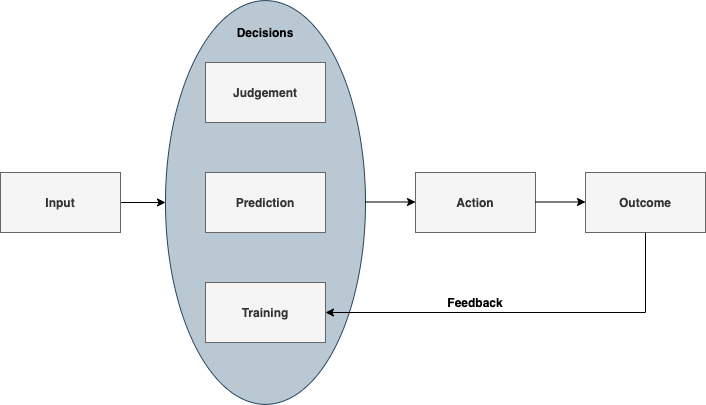

Below, I recreated a diagram from “Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence”, a book that served as a great introduction into the world of AI for me. Going back to the foundations of AI understanding is important because it serves as a starting point into how the technology can be designed for the future, in such a way where people will enjoy their future working relationships with machines. The figure below is not a direct copy from the book, as I changed the middle part a bit, but I believe it still adequately explains everything.

In any task, you start with some input observations, make a decision, act on that decision, and notice the outcome. That outcome acts as experience, as a sort of training, that can be used to form future decisions. Decision-making is split into three areas: judgement, prediction, and training. AI, at least for right now with Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI), deals with prediction. In the TSA example, AI is used to predict when luggage contains contraband like knives and guns.

Judgement is left to the human, especially when there is a human-in-the-loop design, but what happens when the AI predictions are so accurate that human judgement becomes almost entirely reliant on it? Prediction accuracy and judgement reliance, in my mind, are two major factors in determining how susceptible tasks are to automation, though they do not necessarily indicate how fulfilling the job will remain. Still, it is this relationship between judgement and prediction that has been the focus of my thought so far and acts as the basis for the next section.

Before moving on, one more point. In the case of airport security, what is stopping an entire takeover by automation? It is most likely the fact that robotics cannot respectfully go through traveler luggage, or maybe that people are untrusting of robots in search performance. But what happens when these robots become reality and societal values change? Should we ignore these technological advancements because of job loss, or can we ease the transition of creative destruction through meaningful AI design today? I prefer the latter.

Designing AI that Workers Love

The relationship between prediction and judgement, or rather an over-reliance on prediction, is what AI designers and future of work investors should focus on. It is my hunch right now that, even among sizable worker heterogeneity that should not be ignored in research, job fulfillment mainly stems from empowerment and organizational structure. AI tools should therefore be drafted in ways that empower workers and spur organizational camaraderie.

My hunch originates from the U.S. Army, a premier leadership organization that has a principle called mission command. ADRP 6–0 defines it as “the exercise of authority and direction by the commander using mission orders to enable disciplined initiative within the commander’s intent to empower agile and adaptive leaders in the conduct of unified land operations.” This may seem like a stretch right now, but bear with me for a little.

The key is disciplined initiative, of which the explanation is pasted below. In short, commanders give an intent, and subordinates act upon that, free to plan missions and achieve a desired end state. Imagine if managers or executives followed this lead in the future of work; instead of punishing workers when they deviate from an AI prediction, they actually reward creativity and equal working cooperation with an AI tool in order to achieve a task. Some jobs are more easily able to achieve this reality, but designing machine intelligence to give managers this opportunity will thus empower many more workers in the future of work, allowing them to still be decision-makers rather than figurative servants to technology.

But, again, this is just my hunch. I find myself going back to a question I asked above: Why will some people like working with AI and others not? This question gets after the source of job fulfillment. The whole effort to invest in human-centered, ethical AI could be unnecessary if workers only care about their job becoming easier. In that sense, over reliance is the preferred corner solution. For me, I find it to be such an interesting question that I would love to research more in the future.

Below are some more questions I have thought of. Documenting them here acts as a reference for hopeful future work.

Further Questions

- How should we survey firms and their workers about productivity, AI, and job satisfaction in such a way that is unobtrusive and respectful of internal data?

- How do we determine where job fulfillment comes from? Is it from being challenged or the ease of work? How much does heterogeneity within workers matter, or are there jobs that appeal to all kinds of the population? Also, if a majority of workers only want their jobs to be easier, and the market responds by designing AIs that do that, does that not make increased inequality inevitable?

- How does the introduction of AI tools affect our behavior? Should AI tools address the behavioral sciences with nudges or loss aversion measures, or will this exasperate reliance?

- How should the design of AI tools differ between the public and private sectors?

- How does the design of AI in one country affect global trade, especially if other countries are more concerned about economic power and not human well-being?

If someone reads this and has some material that would help answer any of the rambling questions I have, whether in the body or directly above, please let me know. Contact me: Twitter, LinkedIn, Website. Email: james.m.jedras@gmail.com

Okay, throwing these thoughts into the void.

(Important note: None of the thoughts above represent the Army or DoD.)