TLDR: Strict utilitarianism would be a dangerous ethical code for an artificial intelligence to follow based on uncertainty alone. Weighted utilitarianism, where utilitarianism is combined with deontological systems, would be a preferable, although imperfect, alternative.

Utilitarianism is a moral theory that posits what is good is what maximizes collective happiness/well-being. This is often contrasted with “deontological” ethical theories where an action is intrinsically right or wrong based on broader ethical principles rather than on the consequences of the action.

For example, a deontological moral principle may be that it is wrong to lie, steal, or murder under any and all conditions, period end of story, whereas a utilitarian must accept that lying, stealing, or murder could in theory be ethical if the net benefit of said action results in greater cumulative well being than its alternative.

Some argue that there is no such thing as objective morality and that all morality is merely subjective. Personally, I do not find such views satisfactory (I’ve defended moral realism here), and we certainly don’t want to program an AI with no ethical framework; nevertheless, both deontological and utilitarian theories suffer from different flaws.

Deontological theories are too strict. It seems relatively easy to create thought experiments where a small white lie brings about immense benefits. The classic example is that of lying to a soldier in Nazi Germany.

Deontological systems argue that the end doesn’t justify the means, and I generally agree with this. However, that doesn’t mean that the end is irrelevant, or that the end can never justify the means. Let me explain with a thought experiment.

A diabolical AI is programmed to force you to kill 1 person or it will kill 2 people. Since you know this AI will execute its code, there is no uncertainty regarding the outcome. Kill this one person, or two people will die.

Now, a deontological philosopher would simply say, no, I am not going to kill that one person because murder is wrong. And to this, I would agree. However, what if instead of killing 2 people, the AI kills 10 people? 100? 1000? 1,000,000? The entire Earth?

Clearly there is a cut-off point where nearly anyone would become utilitarian, in the sense that they would prefer to live with the guilt (and possible life imprisonment) that they killed one person than to see half of the world eliminated.

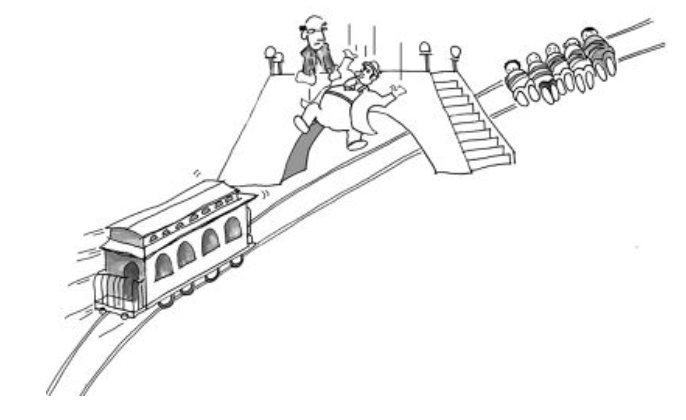

Or consider the trolley problem, where one must decide to change the tracks of a train about to run into 5 people towards the track where “only” 1 person lies. (Or push a fat man onto the tracks to stop the trolley altogether.) If there is only one person on one track, and only one other person on another track, it would seem arbitrary to flip the switch as opposed to letting the “natural” course of events to occur (unless you happen to know the people, of course).

However, as the difference between the number of people on each track increases, most people would flip the switch to minimize the number of deaths.

All of this is to say that deontological approaches to ethics become problematic when big numbers get involved. Would you really not lie to save a thousand lives?

However, strict utilitarian approaches to ethics are similarly concerning. First off, there is the measurement problem of how to actually measure utility. If utility simply means pleasure, then an AI tasked with maximizing conscious utility would create a virtually unlimited number of simple life forms that experience pure bliss (i.e. drug induced coma). That hardly seems like an optimal ethical situation.

A utilitarian can broaden the definition of utility to include more meaningful states of being, such as having friends, living fulfilling lives, experiencing success, and so on. However, how does one even measure this kind of utility? It wouldn’t be a simple scalar value, so perhaps an advanced AI could read everyone’s brain state to determine a utilitarian course of action.

Nevertheless, even if the measurement problem were solved, such that we have an objective measure of exactly what we mean by utility, utilitarianism still faces problems. Imagine that we bred 1000 people for the purpose of scientific knowledge regarding diseases.

No doubt, these experiments could provide immense information about how to eliminate these diseases in a population of billions of people. But what if those 1000 people need to experience excruciating pain in order to derive this knowledge? Under certain conditions, a strict utilitarian would have to agree that the most ethical course of action is to bred these 1000 humans for the purpose of saving millions of lives.

One might counter and say “No! The mere knowledge that these experiments were ongoing would cause much distress to many millions of people, negating the positive benefits of the experiment. So they would not on net be ethical, even to a utilitarian.” But what if this experiment were run in secrecy? No one would have to know where these technological advances were coming from.

Under such a condition, it would appear that the utilitarian must favor a secret program to maximize collective utility. But obviously such a program has the potential to be incredibly unethical, which is why pure utilitarianism is unlikely to be true.

We can see why a super intelligent AI operating on strict utilitarian ethics could easily become a disaster. It could decide to lie to its creators if it estimated the net benefit be optimal. It could create secret concentration camps full of thousands of people if it concluded that to be the “ethical” course of action.

More concerning, this AI system could discover ethical “loopholes” that we can’t even imagine. Do we really want an AI to kill one person merely to save another whose life is “more valuable”? Oh, don’t worry, Baby X is going to be a criminal, and Baby Y is going to be an investment banker.

Importantly, we simply cannot know in advance what kind of ethical conclusions such an AI would draw before running it. It may decide that killing your cat is optimal for social welfare due to complex butterfly effects that a mere mortal couldn’t predict.

On the other hand, programming in deontological values could prove, not merely challenging (see Bostrom on Direct Specification), but catastrophic. An AI that wouldn’t let one person die in order to save millions would probably not be an AI that we want to create.

Is there an alternative approach? Perhaps we can combine the best of deontological ethics with utilitarian approaches. After all, the end doesn’t justify the means, but the end isn’t irrelevant.

Some have proposed “weighted utilitarianism” as an alternative. (To be fair, the linked paper isn’t a rejection of pure utilitarianism in favor of a weighted approach, but instead a way of incorporating cardinal utility for interpersonal utility comparisons, but that is a topic for a later post.)

Without getting into the messy math, (see this interesting paper on some of the math involved in problems with utilitarianism) the basic idea of weighted social welfare functions is that not everyone’s utility should be counted the same.

A poor person values $100 more than a rich person. An elderly person values a seat on the bus more than a young person. A pregnant woman deserves a vaccine more than a healthy man. A homeless person values food more than the average person. And so on.

This can also be extended to deontological principles. Murder, lying, and stealing are wrong except under very limiting situations- self defense, safety, starvation, etc. As such, we should place very high weights towards honesty, life, and liberty without necessarily claiming that they should never be restricted even under extreme circumstances.

Importantly, we could train an AI to discover these weights in much the same way that weights are used to train deep learning systems. There is ample data available for an AI to discover moral truths, and humans can be involved in the training to ensure the system remains safe.

Furthermore, we could create an AI (perhaps through an adversarial network) that tries to find ethical loopholes and asks for human input on what the best course of action would be under hypothetical situations.

This approach is clearly not perfect. Many would object to certain weights, and it is unclear that this system avoids the uncertainty problems that strict utilitarianism follows, although it would avoid some of the more nefarious uncertainty. Nevertheless, it seems like an improvement over pure approaches on either end of the ethical spectrum.

Finally, consider a popular approach for creating friendly AI called “Coherent Extrapolated Volition”.

In poetic terms, our coherent extrapolated volition is our wish if we knew more, thought faster, were more the people we wished we were, had grown up farther together; where the extrapolation converges rather than diverges, where our wishes cohere rather than interfere; extrapolated as we wish that extrapolated, interpreted as we wish that interpreted.

— Eliezer Yudkowsky

In some sense, this is a weighted utilitarian approach. There would be high weights on extrapolations that converge (we would all agree that torture is wrong) and low weights where they diverge (should Republicans or Democrats be in charge?).

One thing is certain. We don’t want to create an AI that would enslave us all for our own good, even if that were the optimal utilitarian calculation. We are destroying the planet and each other, after all.