On a scale of 1–10 (1=not smart, 10=very smart), how smart do you think each of the following three animals are?

I can almost guarantee that you immediately said the dog was the smartest, followed by the hummingbird and then the snail.

Even more interestingly, I suspect you ranked the dog as quite intelligent (ie an 8) and both the hummingbird and snail as not very intelligent (ie a 4/5 at most).

While the first justification you probably give is to do with how big the animal is (and so the assumed size of its brain), there’s actually more to it! In part, you’re drawing on your experience with the animals (which is highly skewed towards cats and dogs thanks to their prime status as pets we can observe 24/7). However, in addition to this, part of how you made your decision is based on the speed at which the animal typically moves relative to you.

This is the concept of anthropocentrism.

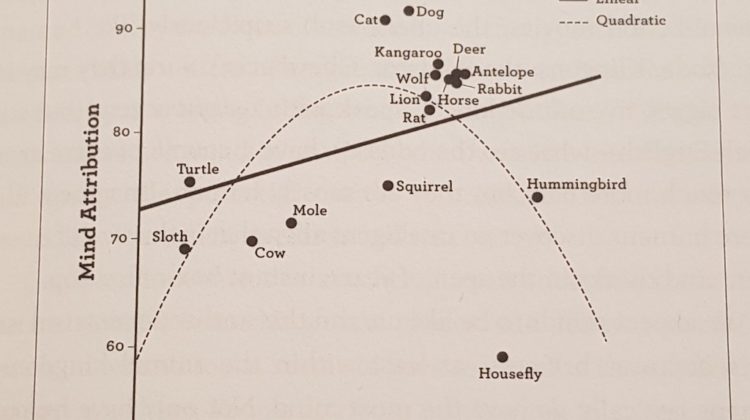

Put simply, our brain looks for things that live life at a similar pace to us. If they move like us, we see them as intelligent just like us. If they move slowly, we see them as less intelligent. Interestingly, if they move really quickly, we’re again left thinking they’re not as smart (likely because we can’t see the patterns as easily and so they appear more random and less like how we humans behave).

Our desire to protect & help animals

How we perceive animal intelligence can have a huge impact on how we interact with them. The smarter we think an animal is, the more likely we are to decide it has a greater right to life and should be protected from harm. Whether encouraging people to become vegetarian/vegan or trying to get people to donate more to animal conservation charities, the animals used in these messages can have a great impact on how easily we can relate to them and therefore how likely we are to respond as the person crafting the message wants us to.

While this can be an interesting discussion around how to effectively change peoples behaviours around how we interact with or respond to animals, what’s perhaps even more important is the way that our perception of speed to calculate intelligence isn’t just restricted to other animals. We do the exact same thing with people.

How this hurts human interaction

While there are a lot of other factors that contribute to how intelligent we think someone else may be, this tool is very powerful in shaping how we assign perceived intelligence to those around us. This is incredibly important because we’re programmed to look for those who are most similar to us, focusing more and more on difference the less the other person reminds us of ourselves.

Have you ever noticed that anyone going slower than you is an idiot and anyone going faster than you is a moron?

Comedian George Carlin

Whether it’s that person dawdling as they shuffle along the sidewalk or the employee who takes twice as long to get a report to you as someone else in the team, people make assumptions about intelligence based on the speed at which others do things relative to how they themselves would. To an energiser bunny sort of person, a couch potato must lack serious brain cells. To a couch potato who is probably more methodical and process driven in their actions, the energiser bunny must be careless and more likely to make mistakes and miss things as they wiz through life.

But it’s not just about the speed at which they perform tasks, it’s the speed they do EVERYTHING.

From how quickly they walk to how quickly they talk, the greater the chasm between yourself and them, the greater the gap in perceived intelligence and the greater likelihood you will do your best to keep them at arms length.

This has implications for almost every new person you meet but is most difficult when entering a new group setting. In order to fit in, you must quickly identify the speed at which those around you are moving, talking and performing tasks. This can be particularly important in forming a first impression when you join a new team or company as it may influence how intelligent and capable others perceive you to be which itself can determine the opportunities presented to you and your ability to fast-track how quickly you can climb.

How this could shape our interaction with technology

Despite not being living, breathing things, we also have the habit of assigning intelligence to robots.

Absolutely, this is much easier to establish when we can see the robot but as AI infiltrates so much of our lives, this is becoming more and more common. From carer robots and pet robots in Japan to chatbots and self-driving cars, the more they act like us, the more we’ll hold them to the same standard as other people.

This is becoming increasingly important as technology infiltrates every part of our lives because it influences:

- how much we expect of it

- how willing we are to persist when it doesn’t do what we want

- how protective we become of it or how quickly we’ll happily dispose of it

Like the chatbot example, it’s feasible to think that the same is true of new tools and technologies we implement in workplaces. By naming, anthropomorphising and creating personalities for these tools so that they transition from being digitised processes into human-like creatures, people will likely become more tolerant of and open to technological initiatives being rolled out in companies and in daily life.

If we know that the physical speed at which something moves alters our perception of its intelligence, what about the speed of thought or processing? Yet to discover much research on this area, one hypothesis may be that it won’t have any effect…up to a point. Just like watching a small child grow up, if the rate of change is gradual, we may come to expect intelligence and processing speed to increase. However, one only has to look at our expectations around companies like Facebook and Amazon to guess that there’s likely a tipping point at which perceived intelligence exceeds our own understanding and comprehension and our expectations around moral conduct change. Unable to understand the intricate analytics driving the actions, people are likely to treat machines like magicians. From an ethical standpoint, our willingness to surrender our freedoms is conditional upon technology subsuming the role of protector much like we did with tribal leaders all those centuries ago. Using our information against us would become a breach of social contracts driving an incredible level of distrust and unwillingness to engage.