Surrounded, concerned and frustrated by our current pandemic, I certainly didn’t want COVID-19 to enter my game-playing time. The virus and its effects had consumed enough of my life.

Confession: I was wrong.

I 100% did not know I needed a COVID-19 game — let alone 51 of them — but I absolutely did. Of course, it helps that these games generally don’t present dark, complex simulations. Also, they were made in collaboration with an arm of the National Academy of Sciences, meaning a number of them contain actual research.

The collection of mostly short vignettes came out of Jamming the Curve, a competition spearheaded by the team behind IndieCade, the yearly celebration of play that would be happening this month in Santa Monica if the events of the world had not intervened. Participants were challenged to build a game from scratch, known in game development circles as a game jam, that somehow reflected our pandemic and the data and science that seek to understand it.

To ensure that these short experiments in game-making were fact-based, the game makers not only had access to epidemiological models developed by Georgia Tech, but also could consult with a team of medical and health experts organized with input from the National Academy of Sciences’ cultural-education-focused LabX department.

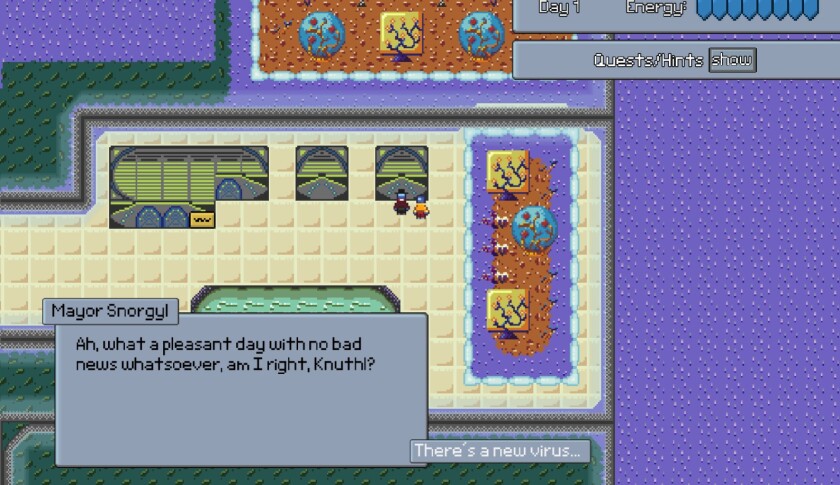

The best of the 51 games felt as if they were opening a dialogue, allowing me to communicate digitally about topics I wasn’t always vocal about, or even desired to be vocal about, in my daily life. Play in this instance became a much-needed exhale, whether I was entering the headspace of someone stubbornly wearing a mask below their nose, trying to stop the spread of disease on an alien planet, witnessing the life of a nurse, or seeing how attempts to control an outbreak among a species is akin to herding cats.

“Cat Colony Crisis,” for instance, is cutesy chaos, as well as the title that won the $20,000 game development grant that was the top prize of the Jamming the Curve event. Don’t assume anything, I told myself, as Ms. Cat, a calico, sneezed. Maybe Ms. Cat just has a preexisting condition? But why isn’t Ms. Cat wearing a mask? And, gosh dang it, why is Ms. Cat starting fights and cuddling with other cats? A pandemic, after all, is no time to behave like cats. Being a cat is no excuse, Ms. Cat!

“Together” is a game that shows how the pandemic can mean very different things to different people.

(Bakiara)

When it comes to educating people about COVID-19, says Rick Thomas of LabX, a big challenge is the invisibility of the virus and the struggle to recognize when we’re making a difference, when we’re being overly panicked and when we’re simply being selfish.

Games, specifically their ability to visualize abstract subjects as well as their need to ask players to lean in and take an active role, can close that gap, says Thomas.

“Games are good to help combat COVID because games do a good job of translating data into stories and helping show people how individual decisions can impact larger issues,” says Thomas. “That feedback is missing in normal day-to-day interactions with COVID. You don’t actually know if you got someone sick by not wearing your mask because there’s a several-day disconnect. You’re not being told whether what you’re doing is harmful, but in a game you can make the connection clearly. That’s why we got involved.”

This is powerful stuff. … If you remember when you were a kid, you learned through play.

Sarah Matthews, epidemiologist

The submitted games — most can be played free via a browser, though some require a download for a PC or Mac — largely avoid the tendency of more mainstream games to put the emphasis on a global pandemic spread and how to manage assets. Here, the games generally have a human focus.

“The Covid Express” feels like my daily life — that is, having to navigate among the unmasked in public spaces or on mass transit. “PandeManager” is more complex, asking you to survive one year as mayor amid shifting policy decisions. “Smash the Curve” is influenced by the classic game “Breakout,” where COVID-19 graphs replace the standard bricks, and power-ups come in the form of masks and contact-tracing.

For those new to the game jam space, be prepared for an amateur, do-it-yourself feel. The games are made quickly, and the goal is to express an idea through play rather than create a slick, finished product. Yet the most polished of the games, such as “Outbreak in Space,” allow players to go deep in experiments with variables.

“Outbreak in Space” is a deep exploration of how to slow a pandemic on an alien planet.

(Patrice Metcalf-Putnam, lpancho, Juan Rodrigues, Kapden)

Against a sci-fi backdrop, “Outbreak in Space” shows us what happens when a certain percentage of the population doesn’t wear masks, isn’t isolated, or continues to engage in activities without social distancing, all of it inspired by access to Georgia Tech’s real-life-inspired simulation equations. But even a simpler title such as “Everyday Hero,” which boasts an old-fashioned arcade feel in which we must keep descending figures distanced and masked, can put a fanciful spin on science.

“People are just walking down the screen and you’re trying to keep them far apart. Then it adds the variable of masks. Then it adds the variable of sick people. Then you have to prioritize,” says IndieCade’s Celia Pearce, a game designer and professor at Northeastern University. Pearce helped organize Jamming the Curve as well as this week’s slate of online IndieCade talks and demos.

“Everyday Hero,” using simple, arcade-like mechanics, illustrates the struggle of staying on top of a pandemic.

(MingXX)

“It’s a little bit of a plate-spinning game, but it uses real data,” Pearce says of “Everyday Hero.” “At the end, you get a number: ‘This is how many people got infected because you didn’t move them far apart.’ That drives home the same game we all play when we go to the market, where I’ll be walking around trying to stay six feet away from everybody. It’s a game that makes you think about your personal space.”

Scrolling the Jamming the Curve Discord channel reveals conversations between game makers and medical experts that feel more like a public health FAQ than a game development event; developers asked questions on a range of topics, including mask efficiency, viral load and persistent immunologic responses.

Some games deal with those weighty topics. “Lab Hero” is a colorful simulation of a medical professional’s challenges and focuses on keeping people distanced, treating patients and researching a vaccine. Others went a more personal route. “Nonessential,” for instance, is an intimate-conversation game about the ways in which we deflect our worries and avoid topics of mental health.

One of the most stressful aspects of COVID-19 prevention, says LabX’s Thomas, is the fact that the most helpful thing to do is often nothing — to stay home and avoid others. “Nonessential” unfolds as a phone call with someone going that route.

“What’s isolation like, and how does that affect people’s underlying mental health problems?” says Seattle-based indie developer Brad Kraeling of his game. “All of this can amplify and stir things up, and bring out a lot of anger in people. I wanted to make a game about someone’s mental health, but in a really casual, talking-to-a-friend way.”

For epidemiologist Sarah Matthews, who spent more than a decade working for the Florida Department of Health and is currently finishing a PhD at the University of Central Florida, she’s already had to work through multiple outbreaks, including the latest. She wasn’t so sure she had much space for games in her adult life, but after serving as a mentor on Jamming the Curve she’s a firm believer, both in how games can reach the public and how they can help health professionals better communicate complex, difficult subjects.

“Nonessential” plays out as a conversation in 2020.

(Brad Kraeling)

“This is powerful stuff,” she says. “Not being a gamer, and looking at it from an outside lens, gave me a new respect for it. This technology can revolutionize how we do things. If you remember when you were a kid, you learned through play. That resonated with me. I recognized that again. You can learn through play. It’s more motivational and more engaging than I first thought.”

She jokes that some of the games, especially those that simulate the public not following health guidelines, can be therapeutic for medical professionals who are seeing their advice go unheeded. The game “Together” dealt with such a topic, showing how the lives of two people with opposite views of the pandemic — one very nervous and another fed up with distancing, masks and closures — will intersect whether they like it or not.

“Together,” says designer Chelsea Brtis, an adjunct professor with the Virginia Commonwealth University’s communication arts department, was a way for her to manage her own frustrations with those she saw not taking the pandemic seriously. It comes, however, from a place of compassion, to help others see a different point of view. The work mirrored some of my own concerns, and I found it comforting to explore them in a game.

“Games give you a kind of safe space,” says Brtis. “I try to approach it so you don’t know it’s a serious game. So you go in with a playful attitude. And games open up the opportunity to have a conversation with yourself when these serious issues are brought in it. The game starts the conversation.”

To play or download any of the 51 games, go to the Jamming the Curve submissions page.

Video Games and Immersive Entertainment

More video games and interactive content from critic Todd Martens.