A new way to pay has arrived in Los Angeles: your face.

As so-called contactless payments rise in popularity during the pandemic, a Pasadena company called PopID is rolling out the nation’s first payment system based on facial recognition at a smattering of restaurants near its headquarters, including mom-and-pop operations such as Daddy’s Chicken Shack and regional chains such as Lemonade.

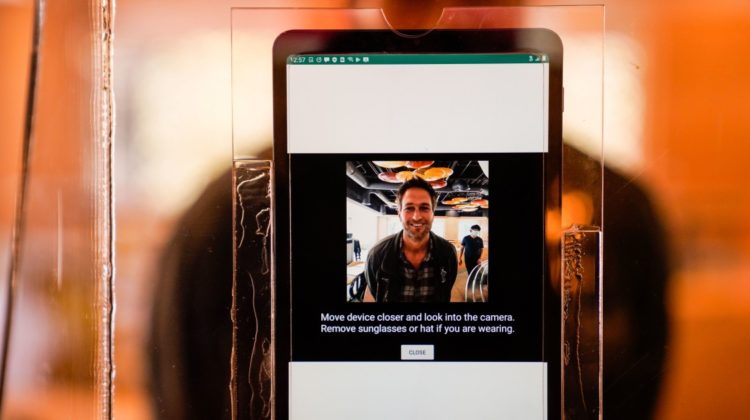

The system is simple: A customer signs up on their phone, takes a selfie and adds cash to their Pop Pay account from a credit card or bank account. When it comes time to pay for their meal, they look into the camera of a PopID tablet or kiosk (no smiling necessary), the cashier verifies their name, and money is withdrawn from the account.

For customers, the experience is eerily seamless, at least when it’s functioning properly. (The software struggles at recognizing faces with masks.)

For restaurants, the service is fast and cheap, assuming customers sign up for it. Easier ordering can speed up lines, and PopID is offering lower fees to process each payment than other payment processing or credit card companies.

In China, more than 100 million people signed up for a similar face payment system in 2019 after 7-Eleven installed it at hundreds of locations, tech giant Alipay is rolling out face payments across the country, and, since July, commuters in the southern city of Guiyang have been able to pay their bus fare using their face.

But PopID’s system is the first to get up and running in the U.S., where facial recognition technology is under intense scrutiny from regulators and privacy advocates.

Eight cities in the U.S., including San Francisco, Oakland and Boston, have banned government use of the technology, arguing that the software is both too powerful a surveillance tool and too inaccurate when finding matches to be safely used by police. During the nationwide protests after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Microsoft, IBM and Amazon all committed not to sell their facial recognition technology to law enforcement, at least temporarily. And Portland, Ore., may soon become the first city to ban even private use of the technology.

John Miller, the 42-year-old Pasadena entrepreneur who founded and runs PopID, didn’t plan on wading into cutting-edge privacy issues when he quit his nanotech job 10 years ago. He just wanted to start a global cheeseburger chain.

“It didn’t take long to realize I’m not very good at it,” Miller said. CaliBurger opened its first location in Shanghai in 2012, advertising Double-Doubles and Animal Style fries, only to get sued for trademark infringement by In-N-Out. The burger chain tweaked the formula and opened dozens of franchises around the world, but seeing the day-to-day difficulties of running a restaurant reactivated Miller’s innovation circuits.

So Miller turned CaliBurger into a testing ground for the future of fast food, spinning out new companies in the process. Miso Robotics focused on labor, betting that robot arms would become cheap enough to install at every fry station to supplement human workers. Kitchen United focused on real estate, betting that restaurants could run delivery businesses out of a citywide network of shared industrial kitchens and quit paying rent on retail locations.

Miller used his CaliBurger fast-food chain as an incubator for new technologies and ventures.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

PopID was Miller’s solution to two restaurant problems at once: slow lines and high fees from payment processing and credit card companies. Those fees can run as high as 3% for each transaction — small change that adds up, considering most restaurants run on 3% to 5% profit margins. Because PopID payments come directly from the users’ preloaded accounts, Miller said, “there’s enough arbitrage built in that we can lower the rates versus credit cards and Apple Pay” and still make money.

“Ten years ago, maybe five years ago, there was no way I’d ever sign up for facial recognition,” said Chris Georgalas, co-owner of the Pasadena fried chicken sandwich shop Daddy’s Chicken Shack. But since Apple started allowing users to unlock their iPhones using their faces in 2018, Georgalas said, the technology has become less intimidating. “The people that use it, they love it, and they come back and they use it again.”

A different PopID product has already found some traction. When the coronavirus began to spread rapidly in the spring, the company quickly adapted its face-scanning tablets to serve as contactless employee check-in devices with built-in temperature screening. Pop Entry, as the system is called, has sold more than 1,000 units in recent months, with several thousand more set to be installed by the end of the year, according to the company.

Lemonade was a Pop Entry customer at a pilot location in L.A.’s Larchmont Village before it installed the face pay system in Pasadena. Now its parent company, Denver-based Modern Restaurant Concepts, plans to install the Pop Entry tablets in all 18 Lemonade locations across California and its separate Modern Market Eatery restaurants in Colorado, Texas, Arizona and Indiana.

Robin Robison, the chief operations officer of Modern Restaurant Concepts, said that employees took to the sign-in system “like a new toy” and that the temperature screenings helped the staff feel safer (though experts have questioned the efficacy of temperature checks in controlling the spread of the virus). After that, she was willing to give the payment system a chance. “Time will tell how many people are using it,” Robison said.

But Miller’s vision for a face-based network goes beyond paying for lunch or checking in to work. After users register for the service, he wants to build a world where they can “use it for everything: at work in the morning to unlock the door, at a restaurant to pay for tacos, then use it to sign in at the gym, for your ticket at the Lakers game that night, and even use it to authenticate your age to buy beers after.”

“You can imagine lots of things that you can do when you have a big database of faces that people trust,” Miller said.

But trust is hard to earn when it comes to facial recognition. Miller said the company is complying with the strictest laws in the nation for face data, the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act, and prioritizes customer consent for all uses of personal information.

A tablet running the Pop Pay system is mounted on a sneeze guard at a Lemonade restaurant in Pasadena.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

Some privacy advocates see an important distinction between government use of facial recognition technology and use by private businesses — as long as the businesses don’t end up giving their data to the government.

That scenario was vividly illustrated in July, when the digital rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation found that a San Francisco business association gave the San Francisco Police Department real-time access to a private network of cameras and cache of footage during the height of the Floyd protests. If police combined access to surveillance footage with access to a database like PopID’s, protesters who used the payment service could be quickly identified en masse.

Nathan Sheard, associate director of community organizing at EFF, said written, informed consent would be key to ethical use of the technology, as well as a clear policy of pushing back when law enforcement comes knocking to request access to the PopID database and informing the user if the company is ordered by a court to comply.

“That’s the minimum type of protections that consumers should be able to expect,” Sheard said. “It’s also good business, if you’re hoping for people to give you information.”

Miller said that level of protection is baked into PopID’s user agreement and basic structure.

Customers choose to sign up for the system and have to click a button or tell a cashier every time they use it, setting it apart from the kind of passive surveillance that most privacy advocates argue is ripe for abuse. PopID’s software also runs on stand-alone devices, which means companies can’t simply connect their own security cameras and start logging their employees’ every move in a searchable database.

Most important, the agreement signed by users when joining the service makes clear that PopID will share user data only when customers explicitly tell it to, whether that means pushing a button to pay or signing up for a loyalty points system with a given shop.

Miller said the company would treat law enforcement like any other third party. If the Los Angeles Police Department came to PopID and asked to run a photo against its database, “our answer to the LAPD would be that we are not allowed to share that information,” Miller said. “We can’t do it, sorry — this is a consumer opt-in service.”

If law enforcement returned with a warrant, Miller said, the company would “fight it as much as we can, until I get something that says I’m gonna go in the slammer” unless PopID cooperates.

Bans on facial recognition have largely focused on government use. But the Portland City Council may become the first to go one step further and ban private companies from using the technology in any area accessible to the public, pending an upcoming vote.

“From our policy [PopID] would be banned,” said Hector Dominguez, Portland’s open data coordinator.

The city’s concern over private use of the technology was sparked in part by news that a chain of local convenience stores had installed a facial recognition system that barred customers from entering the store at night if the software determined their face was a match with someone linked to a crime. The National Institute of Standards and Technology found in 2019 that most facial recognition algorithms had higher rates of false positive matches for women and people of color, and Dominguez and his colleagues worried that the convenience store system would encode racism and sexism into the automatic door.

Dominguez plans to work with industry and local communities to come up with a way to certify the safety of facial recognition tech for private use, but he sees the ban as a necessary first step.

Miller said he is sensitive to those concerns but thinks consumers and businesses can benefit from the technology with the right kinds of protections in place.

“We also want to distinguish between surveillance stuff, security cameras watching you and trying to ID, and our service, which is consumer opt-in,” Miller said. “I think we’d have a pretty good case that we’re the type of facial recognition platform they should be allowing to operate under very careful regulations and policies.”

VIDEO | 06:52

Paying with facial recognition

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.