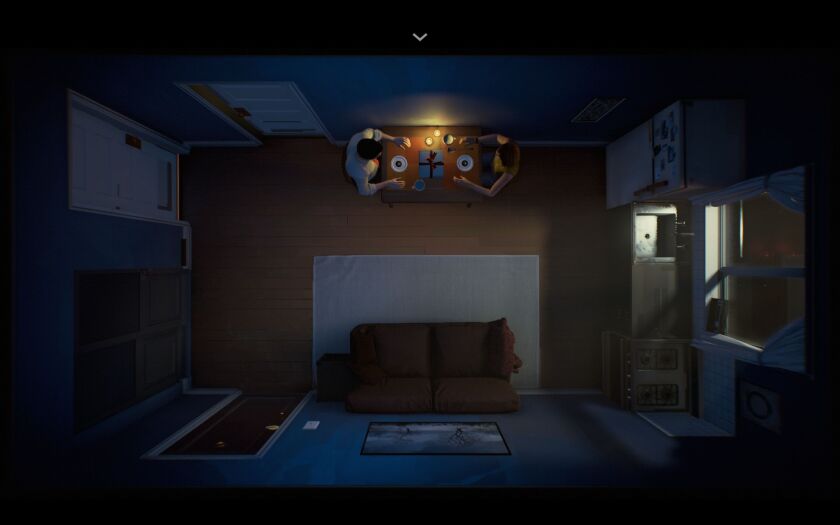

“Twelve Minutes” begins with a revelation. A wife and a husband sit down for a late-night dessert and the wife starts to tell the husband that she’s pregnant.

What happens next will forever change their lives.

Depending on how we play — and the information at hand — expect an intruder claiming to be a cop, accusations of murder, actual acts of murder, a mystery involving a family heirloom, secrets some would prefer forgotten, an apartment filled with hidden compartments and, to conclude, some arguably scary B-movie twists that reveal we’ll never really know those we love the most.

“Things like this just don’t get forgiven,” says the wife, voiced by Daisy Ridley, of the hellish night of traumatic divulgences in which “Twelve Minutes” is set.

“Twelve Minutes” is an exquisitely designed puzzle game disguised as a cinematic thriller, with the stars to match — Ridley, James McAvoy as the husband and William Dafoe as the intruder lead the cast. Its “Groundhog Day”-like conceit — that our main character, the husband, is trapped in a time loop while his wife is accused of murder — reads like a “Twilight Zone” gimmick but becomes more engrossing the deeper we get. The more we discover of these nameless characters the less we truly know (and sometimes want to know). And just when we think we’re getting somewhere — bam! — the game resets.

So when you find a smartphone and think dialing 911 will, if not save you, at least create some game-worthy drama, forget it. Help is 15 minutes away, three minutes longer than the game is designed to last. “Twelve Minutes,” says its director, is about knowledge, but mostly it zeroes in on how our worldview is shaped by our interpretation of the limited facts we have, which become all the more convoluted when human emotions get involved.

Knowledge, in “Twelve Minutes,” is a blessing and a curse.

“Twelve Minutes” begins when a husband and wife sit down to dessert and a revelation emerges.

(Luis Antonio / Annapurna Interactive)

When I started playing “Twelve Minutes,” the latest from Annapurna Interactive, the film studio that is now more or less a game development house, I was rushing through it all wrong. I was looking at the clock, pointing and attempting to click on everything on the screen — “Twelve Minutes” recalls the cursor-driven adventure games of yore (think early “King’s Quest” titles) — in the hopes that I could discover as much as I could as quickly as possible.

But if one dives into a conversation without exploring the apartment and before solving how to converse extensively with both the protagonist’s wife and the intruder, discourse will almost always quickly dissolve into conflict. And if the player-controlled character acts selfishly — that is, demanding answers that will lead to the end of the mystery — characters will respond negatively, realizing they are being put on the defensive.

“When I started this game, I had my first child,” says “Twelve Minutes” creator Luis Antonio. “With kids, we have to teach values to this new human being, but you start to question your own values. What am I going to say to my kid about beating up other people or taking a toy from another kid? The only values I have were the ones given to me, and maybe some of those weren’t ideal. That made me question how the characters talk to one another.”

What Antonio discovered is that communication is often delivered as a series of needs. It’s very easy in the game, for instance, to irritate the wife, and it’s simple for the husband to play the fool, but if one lets go of the idea of the ticking clock and approaches “Twelve Minutes” with patience, conversations between the characters gradually take on a more thoughtful air. And will eventually lead to a love-it-or-hate-it ending that has become a hot topic of social media debate.

All of this came after nailing the looping systems of the game, when Antonio wanted to ensure the players would care about each of the characters. That wasn’t going to happen if we played in a constant state of panic.

Despite the time limit, “Twelve Minutes” doesn’t rush us. The wife spends her evening reading a book on meditation while the husband either tries to prove to her that the time loop is real or to piece together the competing stories of the past that eventually reveal themselves. Sometimes we accrue the most information just by saying nothing. And if we make a mistake, namely when a conversation leads to dead ends, we can walk out the apartment door and instantly reset the loop.

“When you want something, it’s because you have a need not being met,” Antonio says. “When a need is not being met, you try to express that based on the conditions you’ve had as a person. Most people blame others for how they feel. So they’re aggressive. I was trying to deconstruct how people talk, so when there’s a conflict they’re talking from their heart. Not, ‘I hate you because you’re not doing what I want.’ More, ‘I have this need. Would you help me?’ Once that came into place, I adjusted how the characters talk.”

The game is smart — the player, of course, and the husband remember all the prior events, allowing for shortcuts to be revealed. How I first discovered how to subdue the intruder, for instance, was purely by accident — the result of drugging the wife, an act which I at first felt guilty about. And yet the order in which we complete tasks is often important. If you’re going to go through your wife’s stuff, for instance, you had better be sure she’s out of sight.

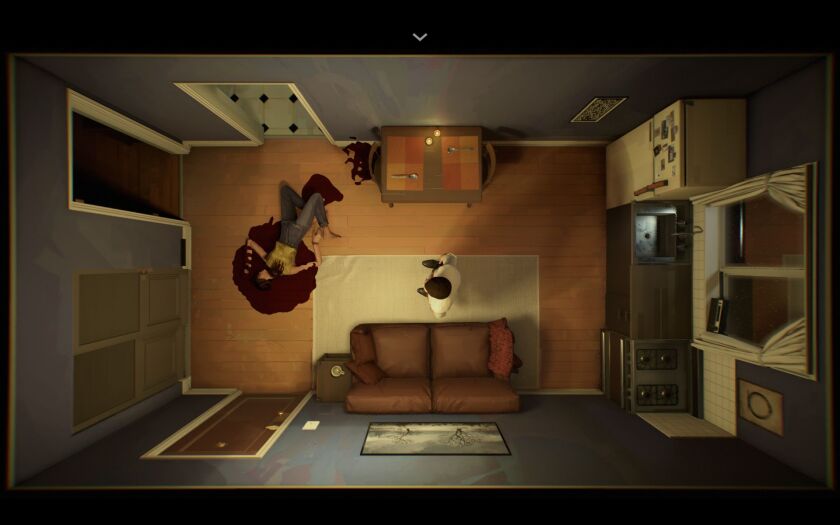

Many of the outcomes of “Twelve Minutes” are disastrous. But don’t worry, the game resets every 12 minutes.

(Luis Antonio / Annapurna)

The compact setting of a one-bedroom apartment, as well as the time limit, results in a game that early on feels Hitchcock-taut. In fact, “Twelve Minutes” to me felt akin to interactive cinema, as its controls are approachable and it feels it would play best in a communal setting. While Antonio, a veteran of Ubisoft and Rockstar Games before going independent, says he can imagine the narrative as a movie or TV series, its structure as a game helps make the exaggerated scenarios of “Twelve Minutes” feel personal.

“It could work as a film or a book, but you wouldn’t have the most interesting aspect,” he says. “It’s you the person making the choices, and you’re making those choices based on your interpretation. There will be a point where the game becomes subjective. You won’t get a, ‘OK, you won the game!’ So did you arrive at the resolution? Or is it a resolution for you? Should you go further? I think how you treat the characters and how you build those layers, that’s your own.”

But that ultimately elevates “Twelve Minutes” from a nifty thriller to one of the year’s most debated games. The tight setting and therefore the bulk of the so-called action — the events of the past that create the drama of the game — live in our imagination. Facts, such as they are, are the words of three people with stories to hide. And yet that mirrors the relationships of the characters in the game.

In other words, how we act and how the characters act is often one and the same, as we’re simply directing the husband to look, talk or use an item. Everything else is often in his head. No matter how amplified, savage or romantic the scenarios get, the game will likely have him starting all over in a matter of moments.

As he repeats the acts — a metaphor essentially for dwelling on them — we realize our mind is maybe not always a great place to be.